A 2007 bottle of Chateau Haut-Brion Premier Grand Cru Classe. Source: Domaine Clarence Dillon via Bloomberg

The facade of Chateau Haut-Brion in France. The wine produced at Chateau Haut-Brion is one of the world's five rarest and most costly investment wines. Source: Domaine Clarence Dillon via Bloomberg

Fate bequeathed a delusional legacy to the small French suburb of Pessac.

As the 1st century A.D. birthplace of Bordeaux wine, Pessac’s Gunzian gravel soil over the millennia has attracted holy men, scoundrels and a crowd of billionaires on a quest to spend beyond $5,000 for a vintage bottle of Chateau Haut-Brion Cru Classe de Graves Premier Grand Cru Classe Appellation Pessac-Leognan Controlee Domaine de Clarence Dillon SA.

It’s an expensive mouthful.

“There’s not one explanation for how it happened,” says Jean-Philippe Delmas, the “regisseur” or estate manager of one of the world’s five rarest and most costly first-growth investment wines. “In the end, it’s all up to Him,” Delmas adds, pointing an index finger toward the heavens, as did his regisseur father and grandfather before him.

It all began more than 2,000 years ago, when a group of Bituriges Vivisci tribesmen scattered grape seeds a few miles west of the Gironde River. That gesture has burgeoned into a hyper-luxury, billion-dollar industry hinged on how the weather affects the 400,000 vines that annually turn out between 10,000 and 11,000 cases of Haut-Brion.

Strolling through snow flurries to inspect his 124 acres of spindled vines, Delmas, 41, considers the expense of maintaining one of Bordeaux’s signature estates. “There are no rules on the cost of making Haut-Brion,” he says.

Rare Whites

Still, the arithmetic remains precise: Each plant produces 50 centiliters or 1.05 pints of red. A further 6.5 acres annually squeezes out what Delmas says is an even rarer and can be more expensive 5,000 to 6,000 bottles of Haut-Brion white, which sells between 251 euros ($331) and 3,049 euros a bottle, depending on the vintage.

Delmas exclusively sells the wine that

Thomas Jefferson in 1787 first imported to the U.S. to Bordeaux’s 70 registered wine merchants at a 5 percent to 10 percent markup. Though Haut-Brion prices trail first-growth investment rivals Lafite-Rothschild, Mouton-Rothschild, Latour and Margaux in classic years such as 1982 and 2000, the brand outshines its competition in the 1945, 1959 and 1989 vintages.

The 1989, for instance, fetches an average merchant price of $18,075 a case, according to the London-based wine exchange Liv-ex. That’s about 50 percent more than a 1989 Lafite and more than triple the prices asked for other first growths.

Hong Kong Sale

Off the investment floor, Christie’s International Plc in London last November sold a case of 1959 Haut-Brion for $20,900. A dozen of the chateau’s 1945 bottles in May pulled in $48,800 at an Acker Merrall & Condit sale in Hong Kong. The Liv-ex says says the average current European broker price for a single bottle of 1945 Haut-Brion is $5,027.

As for the street value, “billionaires don’t care about money,” Delmas reckons.

To be sure, Haut-Brion never has been a bottle for the bargain bin. Faded records in the Pessac City Hall indicate that Lady Johanna Faure on Sept. 6, 1426, was the first to register the cultivation of vines in Haut-Brion for the monks of Menuts to commemorate the death of nobleman Johan d’Artiguemale.

On April 23, 1525, criminal-court clerk Jean de Pontac was gifted the grape field as part of his dowry, more or less creating the Haut-Brion brand. Owners since have included former French Foreign Minister Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand, who sold the estate to a banker, who then sold it to a stockbroker, who sold it to another banker, who in 1935 sold it to New York financier Clarence Dillon.

Pricey Pitcher

No wonder a “flagon” of Haut-Brion for centuries has cost more than a milk cow. Indeed, the 17th-century English writer

Jonathan Swift noted in his diaries that he paid 7 shillings, the price of a cow, for a pitcher of Haut-Brion. Philosopher

John Locke in 1677 visited the chateau for a taste and pronounced the claret a rip-off.

“Thanks to the rich English, who sent orders that it was to be got for them at any price,” is how the father of liberalism described Haut-Brion’s market forces at work.

“I don’t know what to do about it,” Delmas rues. “We have more investors than drinkers as clients and I’m sad about that because we make our wine to be drunk. We have fewer and fewer clients, but all of them are billionaires.”

Growth Markets

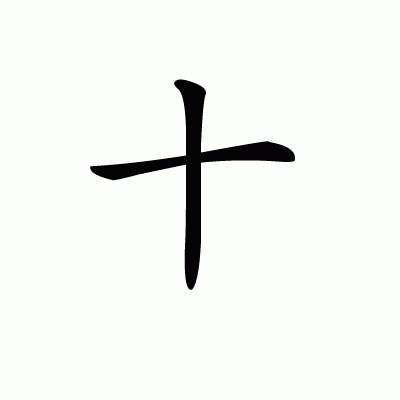

Just who those billionaires are might be easy to discover if you can decipher the Chinese characters scribbled on page after page in the leather-bound Haut-Brion guest book. “China and Asia are the growth markets,” Delmas says. “That’s where the money is.”

Delmas says that Haut-Brion posted its first profit in the 1970s. “The Dillon family kept giving us operating capital,” he explains. “My grandfather fought to make as much wine as possible. I fight to reduce the volume and have no excuses for producing a bad vintage.”

Haut-Brion has had an undisputed place among the top 10 or 20 most expensive wines in the world for the past 350 years, yet it tends to sell for less than rival top reds from the Medoc, Saint-Emilion and Pomerol.

“Haut-Brion has definitely lagged behind vis-a-vis first growths,” says William Grey, manager at the London-based

Wine Investment Fund, which has 42 million pounds ($66 million) under management. “It’s got a great track record. It would form part of most people’s portfolios because of the quality of the wine. It’s lagging at the moment, which could make it the best deal.”

Wall Street Link

Stephen Williams, founder of the

Antique Wine Company who commutes between London, France and Hong Kong selling top claret to high-net-worth collectors, says Haut-Brion prices have been held back by its lack of a strong reputation in China, coupled with reduced demand in recent years from its traditional U.S. customer base, a clientele that reflected the Dillon ownership and Wall Street connection.

“The most sluggish wine market has been the U.S., so Haut- Brion is going to be the first of the first growths to suffer from that,” says Williams. “The wine has the quality, but the brand doesn’t have the presence in China.”

That may represent an opportunity for investors looking for alternatives to top-selling Bordeaux such as Chateau Lafite or Latour, or cult wines like Le Pin. “From a value perspective, Haut-Brion is definitely the wine to buy,” Williams says. “It’s the same quality as the other first growths and half the price.”

Private Stash

As for those billionaires, Delmas says they come from all over and have no scruples about scoring any of the approximately 2,000 bottles of red and 1,000 bottles of white annually kept in the estate stash. “I get calls every day,” says Delmas, who declines to disclose the details. “Let’s say that billionaires will do anything to try and acquire an extra case or bottle of Haut-Brion. I am firm.”

Back in the vineyard, Delmas shakes his head, exhales a plume of cold breath and smiles. “I’m also lucky,” he says. “I can drink Haut-Brion.” The chateau’s 75 employees also get to taste the good stuff. And to ensure the flow continues, workers each year replace some 4,000 vines, each one taking 10 years to become part of the grand cru bloodline.

Luc Nicholas calls the creation of Haut-Brion a wedding. He’s the 47-year-old cooper charged with the delicate ceremony of “bousinage,” the burning of the barrel. Nicholas constructs 640 Haut-Brion barrels a year, all fashioned from planks of French sessile oak cured for 3 years.

“The marriage of the wine and the oak is what makes Haut- Brion,” Nicholas says, fixing traditional chestnut rims on his barrels. “The inside of the cask must be burned to create the proper taste. Not too much, not too little.”